Givens

November 5–December 17, 2016

AA|LA, Los Angeles

manuel arturo abreu, Julie Ault and Martin Beck, Cristine Brache, Patty Chang, Raque Ford, Lina Viste Grønli, Ravi Jackson, Patrice Renee Washington

-

-

manuel arturo abreu

manuel arturo abreu

-

Cristine Brache

Cristine Brache

-

Cristine Brache

Cristine Brache

-

Raque Ford

Raque Ford

-

Raque Ford

Raque Ford

-

Patty Chang

Patty Chang

-

Lina Viste Grønli

Lina Viste Grønli

-

Ravi Jackson

Ravi Jackson

-

Ravi Jackson

Ravi Jackson

-

Patrice Renee Washington

Patrice Renee Washington

-

manuel arturo abreu

manuel arturo abreu

Givens begins with a few simple juxtapositions: a fresh fig placed atop a text on social ethics from the 1970s; a pink tallow candle from a local botanica, set into the tab of a can of guanabana juice.

The artists in the exhibition take certain givens and subtly upend them to reveal underlying truths about everyday reality, and how power manifests unevenly within it. The fig and book comprise Lina Viste Grønli’s Fig on Roles and Values, which hints that social codes, and perhaps meaning itself, might be arbitrary at their core. And the combination of candle and juice can in manuel arturo abreu’s Herramienta confronts the methods and codes of contemporary art with alternate temporalities: the impermanence of abreu’s found-object assemblages and the rituals—presented here as commodities—of the artist’s Dominican heritage. Of course, the logic of contemporary art is what renders these works legible as more than just banal collections of things, even as this legibility derives from, and enforces, the framework of a white Western subject-position.

The included works reframe relations between subject and object through subtle material manipulations. They consider how a body or an object—in itself or as a cipher for a non-normative body—experiences its subjection, the violence inscribed on its surface. This inscription occurs literally with Brache’s mother-of-pearl key and keyhole, the word “Hole” engraved on it in a collision of function, luxury, and the threat of sexual objectification. More obliquely, Patrice Renee Washington’s ceramic basin filled with bleached flour—pointedly titled Oppressional Fixture #1 (Feed Trough)—alludes to whiteness as a hegemonic cultural imperative. And Patty Chang, in her video Eels, writhes uncomfortably in front of the camera with live eels under her shirt, subjecting her body to a concealed, durational (and perhaps libidinal) violence that echoes the operations of power on gendered, racialized subjects.

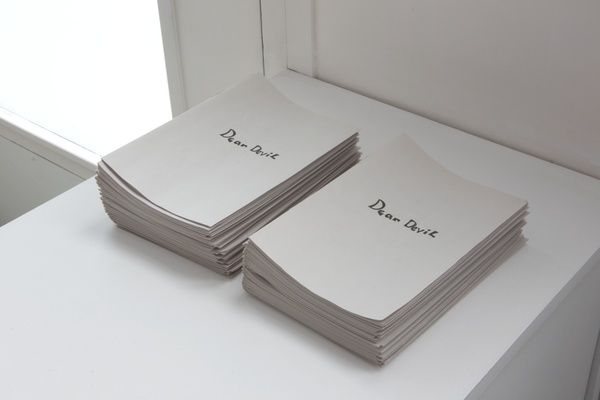

Language can also recontextualize familiar forms or point to the violence embedded in them. Text appears throughout the exhibition, subtly or confrontationally, as process or found object—as in Raque Ford’s work, which materializes an epistolary narrative in paint and red plexiglass, and Ravi Jackson’s use of LeRoi Jones’ early writings in his sculptures and paintings—and writing forms a part of the broader practices of several of the included artists. The grammar of the gallery space, too, is quietly manipulated with Julie Ault and Martin Beck’s Pink Ceiling, which becomes a sort of frame, extending the recontextualizing gesture to encompass the entire exhibition. Together, these works reveal that arrangements—of spaces, words, objects, bodies—are never neutral, but marked by processes of submission, subjection, oppression, and resistance.