If you want to do something, forget this debt, and remember it later.

10 February—1 April, 2017

Celaya Brothers Gallery, Mexico City

Lene Adler Petersen and Bjørn Nørgaard, Hannah Black, Paloma Contreras Lomas

-

-

-

Lene Adler Petersen and Bjørn Nørgaard

Lene Adler Petersen and Bjørn Nørgaard

-

Hannah Black

Hannah Black

-

Paloma Contreras Lomas

Paloma Contreras Lomas

-

First, I want to note two things that might or might not be obvious:

-

That capitalism, or the debt that it runs on, demands fixed identities: you must remain the same person—with the same fixed and knowable name, race, gender, and so on—in order that the capital you owe can be extracted from a future you. Capitalism forecloses a future self that might differ from, or revolt against, its present.

-

That value adheres differently to different bodies according to these historically sedimented classifications of race, gender, class, and so on that capitalism demands in order to further its consolidation of wealth and power in the hands of a few, and to make this brutal consolidation appear just.

The artist and writer Hannah Black asks: “What happens when these principles of [capitalist] accumulation are given flesh and walk around?” (Artforum, October 2015).

If you want to do something, forget this debt, and remember it later. is an exhibition titled after a line from Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons. Works in the exhibition by Black, Lene Adler Petersen and Bjørn Nørgaard, and Paloma Contreras Lomas navigate the ways in which bodies are shaped by and resist flows of capital, determinations of value, and inescapable debt.

In May 1969, Lene Adler Petersen walked naked through the Danish stock exchange carrying a wooden cross in one hand. Her performance, entitled Den Kvindelige Kristus (The Female Christ), was documented by her husband, filmmaker Bjørn Nørgaard; the brief clip was included in a collaborative film he made the following year, from which the footage on view is excerpted. It’s often understood as a gesture feminizing the figure of Christ to confront rigid patriarchal capitalism with spiritual, feminine softness, logic with erotics. I want to suggest that the work allows for an infiltration to take place between the two sides of this (gender) binary, drawing out the ways in which all bodies are unevenly imbricated within the structures of capitalist exchange. More than this, Den Kvindelige Kristus attempts to navigate the deeply interlinked histories of capitalism and Christianity, and the gender norms they often violently enforce.

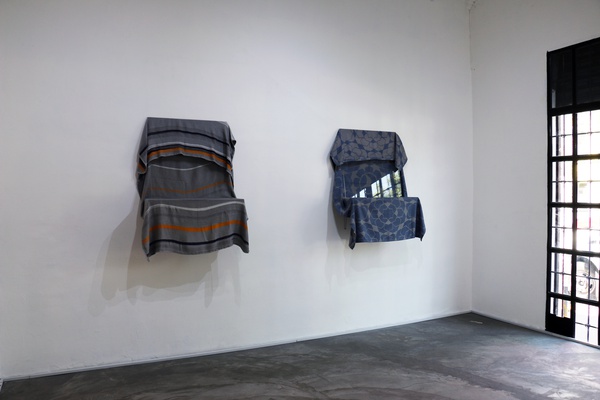

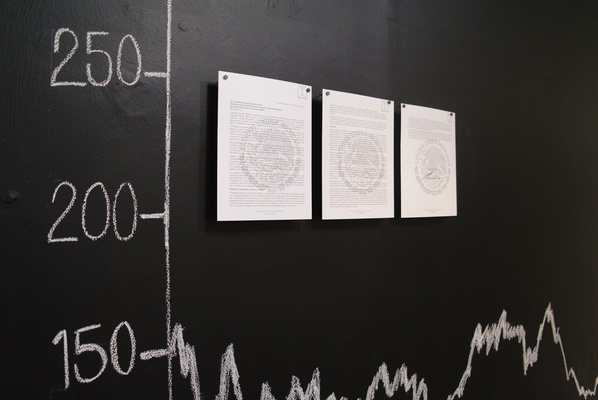

Lomas' ongoing project Fidel Velzáquez No Esta Muerto traces the materiality of production, manifesting as a cloud of metallic dust on the bodies of laborers in Mexico’s national mint, as they in turn produce currency, value made material. Black’s sculptures, as well as her videos My Bodies (2014) and Credits (2016), similarly consider how bodies signify, circulate, and accrue or are denied power. The sculptures seem to accommodate the human body—draped with airline blankets, they slightly resemble chairs—but they travel much more freely than most people and, on display, they offer little warmth or comfort. Debt is central to Credits, which follows a masked fugitive through a wilderness both real and imagined, in a capitalist present that extends into the past and future, foreclosing alternatives.

In The Undercommons, Moten and Harney seek instability or what they call fugitivity—a refusal of the imposed stasis of identity and the creditor/debtor relation with origins in Black radical thought, in the figure of the escaped Black slave. “Fugitive publics,” they write, “need to be conserved, which is to say moved, hidden, restarted with the same joke, the same story, always elsewhere than where the long arm of the creditor seeks them, conserved from restoration, beyond justice, beyond law, in bad country, in bad debt.” They insist on this bad debt, debt that gets forgotten and can’t be repaid, debt without credit, without creditors; they advocate survival through reliance on our unpayable debts to each other.

I’m not sure an exhibition can itself advocate bad debts, forgotten debts—the process of making an exhibition is too bound up in the exchange and accumulation of capital (financial, social, and otherwise), in affixing value to objects but also to identities in along the same lines of white supremacy and patriarchy that structure the world at large. We shouldn’t forget this. Our shared bad debts, on the other hand—or as the narrator of Credits declares, “In a world exactly like this one, the indebted escape.”