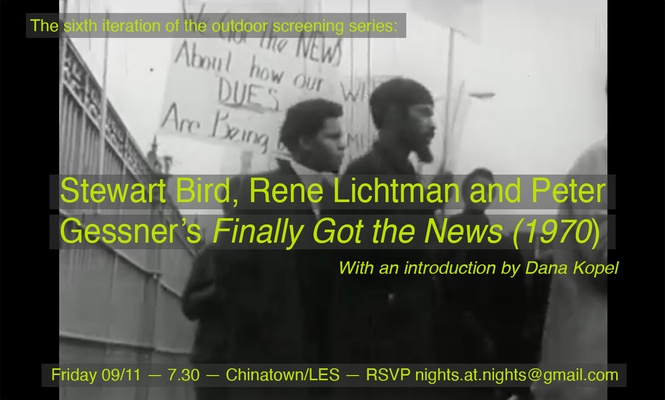

Finally Got the News, 1970

Directed by Stewart Bird, René Lichtman, and Peter Gessner

Produced in association with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers

Screened as part of Nights at Night, New York, 11 September 2020

My introduction to the screening:

I’m excited to present Finally Got the News, which is a documentary from 1970 directed by Peter Gessner, Rene Lichtman, and Stewart Bird, and produced in association with its subject, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. The creation of the film, and who’s responsible for it, is actually a bit more complicated than that: Gessner, Lichtman, and Bird were members of the New York–based radical film collective Newsreel. All three were white, and they went to Detroit in 1969 with Jim Morrison (another Newsreel member) to compile documents and record conversations with Mike Hamlin, John Watson, Ken Cockrel, and other members of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, or DRUM, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in order to encourage Newsreel to finance the film. The New York Newsreel crew liked the material but was hesitant to fund the film project, so Morrison started smuggling hash in order to raise money for the film; unfortunately, he was arrested at the US-Canada border and sentenced to a decade in prison. The other three ultimately went to Detroit, supported by Newsreel, along with another group of collective members who were less interested in documenting the League’s activities and more interested in imposing their preferred strategy—taken from the Black Panthers and the Weathermen—on organizing in the city.

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers was reluctant to build a more public profile—and to work with white filmmakers to do so. League cofounder John Watson and others were open to working with the trio of directors but insisted the approach shift from a “reporting framework” intended to bring information to Newsreel’s largely white audience to an educational one directed at the Black workers in and around the League. I think this is where some of the film’s didacticism comes from: the final scenes feature a voiceover narrative detailing the League’s aim to organize all Black workers in the US as a class and the necessity of linking that goal to global anti-imperialist struggle. To be clear, I don’t think the film is didactic in the sense of boring or patronizing. I mean that the film was created not to depict the struggle led by Black workers in Detroit, but as a tool in that struggle.

I draw a lot of this background from Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin’s Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, which is a history of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. You’ll hear, at the beginning of the film, the song from which the book takes its title, originally written in 1965 by Joe L. Carter while he was a production line worker at the Ford Rouge auto factory. The title of the film, Finally Got the News, comes from a chant led by General Baker during the union elections at the Dodge Main plant in 1970, which starts: “Finally got the news / how your dues are being used…”

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers formed in opposition to not only the exploitative owners and managers of the auto factories in Detroit, but also the indifferent at best, often anti-Black union bureaucracy of the United Auto Workers. The UAW formed in Detroit in 1935, building worker power through actions like the 44-day Flint Sit-Down Strike against General Motors in 1936–37. Following World War II, however, the major car manufacturers—GM, Ford, and Chrysler—made a deal with the UAW, emphasizing profit and productivity and neutralizing the union’s radical origins. Walter Reuther, the legendary UAW president from 1946 to 1970, is quoted as saying, “We make collective bargaining agreements, not revolutions.” This is also the era of the second Red Scare and McCarthyism in the US, which purged a huge number of communists from the labor movement.

The auto manufacturers often refused to hire Black workers, and when they did, as in the early 1960s, Black workers were given the most grueling jobs—in the body shop and the foundry—at the lowest pay. Companies like Chrysler would exploit a loophole in which workers were only protected by the union contract after 90 days of employment, firing mostly Black workers on their 89th day; the UAW, which received dues and initiation fees from the workers regardless, allowed the practice to continue. Racism was so explicit that sick notes signed by Black doctors were considered inadequate. In the late sixties, Chrysler also started hiring Arab immigrants, subjecting them to similarly inhumane and racist conditions.

95–100% of foremen and superintendents at the factories were white, and leadership of the UAW was overwhelmingly white as well, though Black workers represented around 30% of the union’s membership. Black workers at Chrysler’s Dodge Main plant formed DRUM, the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, in May 1968, to address dangerous conditions, exploitation, and anti-Black racism within both the factory and the union that was ostensibly meant to protect them. DRUM advocated and practiced direct worker representation towards revolutionary ends, and spurred the creation of a number of similar worker groups at other factories, including FRUM (Ford Revolutionary Union Movement) at the Ford River Rouge Plant, and ELRUM (Eldon Avenue Revolutionary Union Movement) at the Chrysler Eldon Avenue plant. Though DRUM focused on Black workers at Dodge Main, they offered clear analysis—as you’ll see in the film—that their organizing served the interests of all workers.

On May 2, 1968, Black workers initiated the first wildcat strike—a work stoppage not sanctioned by the union—at Dodge Main in 14 years, shutting down the plant. A front-page article in the June 1968 issue of Inner City Voice, Detroit’s Black revolutionary newspaper, delineated the problems of Black workers in the union as follows: “The UAW with its bogus bureaucracy is unable, has been unable, and in many cases is unwilling to press forward the demands and aspirations of black workers. In the wildcat strikes the black workers on the lines do not even address themselves to the UAW’s Grievance Procedure. They realize that their only method of pressing for their demands is to strike and to negotiate at the gates of industry.”

From the beginning, Finally Got the News posits the struggle for Black liberation and worker justice as fundamentally interlinked—just as the League did. Their organizing focused on Black workers as agents of revolutionary change—unlike better-known radical formations from the late 1960s and early 1970s like SNCC, the Black Panthers, or Students for a Democratic Society, which prioritized students, youth, or, a vanguard party. The film opens with a montage of imagery of chattel slavery in the US, and then photographs of white and Black workers in early auto factories, as well as labor struggles within those factories—and the violence of police brought in to put down those struggles. John Watson speaks the first words of the film, explaining: “Black workers have historically been the foundation stone upon which the American industrial empire has been built and sustained.”

The film then situates us in Detroit with a map showing the Rouge River dividing Henry Ford’s territory from the segregationist suburb of Dearborn, Michigan, and close-ups of Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals from the early 1930s. Like Rivera’s murals—which lambast auto barons like Ford and suggest the revolutionary potential of workers—Finally Got the News is explicitly ideologically driven. The film, like the worker-organizers who are its subjects and in a sense co-creators, at once illustrates and lays some of the groundwork for a Black worker–led revolution that would also be Marxist and internationalist. Watson traveled to Europe to try to distribute the film more widely; he sold copies of it to the Italian Communist Party and several extra-parliamentary groups in that country.

Towards the end of the film, brief segments on the relationship of Black workers’ struggle to the white working class as well as the particular challenges facing Black working women in Detroit gesture towards some of the less-explored dimensions of working-class organizing. There are obvious echoes of the present throughout: beyond the blatant exploitation of largely nonwhite workers that continues today, we witness scenes of a smashed up and graffitied city block following the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, with pigs shoving Black people into cop cars. The directors also dedicate a short segment to the protests that followed the killing of Danny Smith, a nine-year-old Black child who was shot by a cop’s stray bullet while waiting for the bus. The League helped organize the community’s fight for justice following the murder. I hate to describe the film as more relevant than ever, which is usually a bullshit phrase thrown around by museum marketing departments, but it’s jarring to watch Finally Got the News after four months of Black-led mass uprisings sparked by the murder of George Floyd and others by cops and to reflect on how little has changed—how entrenched, how foundational anti-Blackness is to every aspect of work and life in the United States.

As a newly minted professional union organizer, as a communist, and as a white person who is alive right now, I’m thinking almost incessantly about the ways in which labor, race, capital, and policing reproduce each other, often violently. Where do we go from here? How do we best struggle against the immeasurable brutality of racial capitalism? I’m reminded of something Rachel Herzing, one of the founders of the abolitionist group Critical Resistance with Angela Davis and others, said in an interview in 2016: “If you don’t engage with decades of previous organizing, if you don’t engage with where you are falling down, then you will make the same mistakes over and over. You will make mistakes made a month ago. You will make mistakes that were made ten years ago. You might make those anyways, but they might be more productive mistakes if you’ve made a commitment to studying movement history.” My hope in sharing Finally Got the News isn’t just that it teaches us about the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and their crucial but underrepresented struggle, but that it helps us make more productive mistakes.